The search for an appropriate early care and education setting that meets a family’s needs while also attending to the growth and development of young children can be a daunting process. For state child care administrators interested in supporting access for vulnerable children and families, it is imperative to establish a valid and reliable measure of accessibility.

Researchers studying the impact of early childhood education and care programs have confirmed that children and families who access truly high-quality services achieve positive outcomes that last a lifetime. Children and families with vulnerabilities such as socio-economic status, developmental delays or special needs, often thought of as at-risk for difficulties in school and negative life outcomes benefit significantly from access to high quality early childhood education and care. Unfortunately, the families that have the most to gain from access to high quality programs have difficulty finding and enrolling in them.

As state and federal policy makers work to identify policies and practices that support accessibility of high quality care and education services, their current efforts are somewhat stifled by a lack of tools to adequately measure whether or not children and families have reasonable access to services. With this challenge in mind, Dr. Herman Knopf, Research Scientist at the Anita Zucker Center, in collaboration with Dr. Vasanthi Rao and Mr. Phillip Sherlock at the University of South Carolina, have begun development of a “Child Care Access Index (CCAI)”. The CCAI will be helpful as a support for state child care systems’ compliance with the Child Care Development Block Grant reauthorization of 2014, which requires states receiving Child Care Development Funding to strategically invest to increase accessibility of high quality services to vulnerable populations. Dr. Knopf and his research team are helping states document the extent to which quality child care is accessible to families of young children receiving child care subsidy.

I sat down with Dr. Knopf to learn a little more about the accessibility index, it’s importance, and his vision for the future of data-driven policy decisions.

Alexis Brown: Hello Dr. Knopf, thank you for agreeing to speak with me about your Child Care Accessibility Index (CCAI). So what does the index do?

Dr. Knopf: “Our access index is a way for states to measure the extent to which there is access to high quality childcare for families who are using child care subsidy, and then track the accessibility of services over time. The CCAI is designed to help policy makers identify areas where access is good and areas where access isn’t as good, so that they can better target policy interventions to areas where they are needed. In addition, the CCAI will be used to measure changes in access over time so that state policy makers can evaluate the effectiveness of policy and practice changes as they support (or not) increased access to high quality early childhood education and care. Currently, state child care administrators don’t really have a way of identifying that.”

AB: What inspired the development of the CCAI? Why is this project important?

DK: “Our research team in South Carolina had been working closely with the state child care administrator in South Carolina, and she wanted to target resources to increase accessibility, but she didn’t have a way to measure it or identify where resources should be directed.

So, the dilemma was, she wanted to make data based decisions, but she didn’t have a good measure to use to inform her decision. So, what we’re doing is trying to construct a measure of accessibility that is stable, in that they [policy makers and government stakeholders] can rely on the measure to make these important policy decisions.”

AB: Can you paint a picture of how a policy maker would interact with the index?

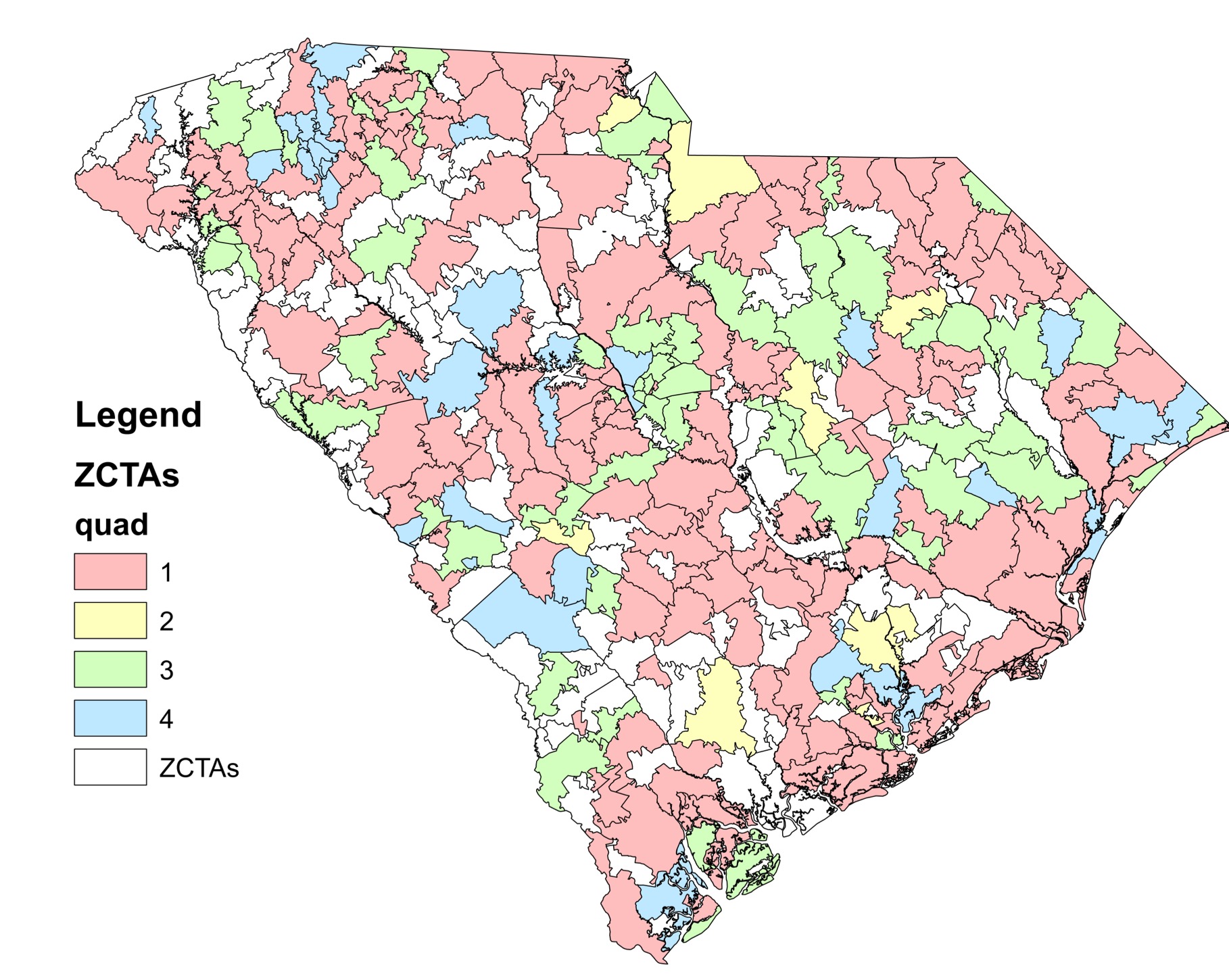

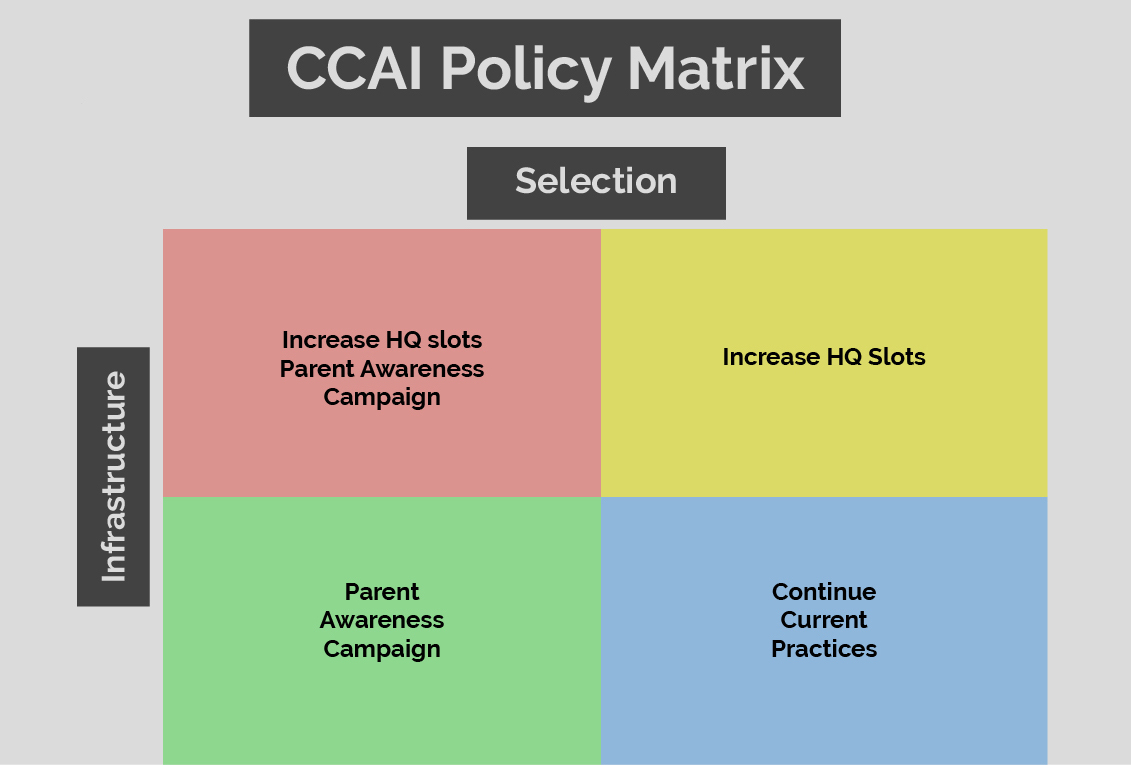

DK: “The CCAI is composed to two sub-indices: the Selection Index and the Infrastructure index. The Selection index measures the extent to which families are selecting the best available care within their area. Using straight forward arithmetic we compare the choices that parents make within their home zip code with the available choice set. The result is a number that indicates the strength of parent selection practices. A positive number indicates that parents are making a good use of the quality choices in their zip code, while a negative number indicates that parents are not selecting the best care that is available to them.

The Infrastructure Index measures whether or not an area has the capacity within high quality programs to enroll all of the children using child care subsidy. In this measure we look at the actual number of slots in quality programs and subtract the actual number of children using child care subsidy. If the difference between slots and children is negative then the zip-code does not have the necessary infrastructure. If, on the other hand, the difference is positive, then the zip code has the capacity to serve more children in higher quality early childhood care and education.

To increase the understandability of these measures we have constructed a map that is color coded to reflect different accessibility patterns and a potential policy intervention matrix to help provide guidance to child care administrators.

AB: Okay, I’d like to learn a little more about your personal connection to the project. You seem to have a strong connection to work which informs policy-level change. How’d that come about?

DK: “While I have been engaged in work related to quality early education and care for my entire career as a researcher, I’ve gradually migrated into work more directly related to policy in recent years. Early on I was focused primarily on defining quality from multiple perspectives such as parents, child care providers, teachers, and policy-makers, and exploring the linkages between the things that we could measure, the characteristics that parents and child care providers attend to, and the impact of these services on children.

As the field has started to reach some consensus regarding the characteristics of high quality services that support positive child outcomes, I moved into work endeavoring to identify the things that we can do to increase quality. I started focusing more on systems that support quality enhancement, such as professional development systems. As I engaged in state-wide technical assistance and professional development systems development in South Carolina, I became more connected with the South Carolina Child Care Administrator, Leigh Bolick. Together, we began to investigate the way that multiple systems within the South Carolina Child Care Program interacted with each other and eventually established the SC Child Care Policy Research Team which consisted of myself, Ms. Bolick, Dr. Rao, Ms. Diane Tester, and doctoral students Mr. Phillip Sherlock, Ms. Wenjia Wang, and Ms. Fan Pan. Through this initiative I became more involved in informing policy decisions.”

AB: You used to be an early childhood teacher, tell me about how those experiences shaped your work today.

DK: “My early experience as a teacher and as a child care administrator have definitely helped me to remain more grounded when working with policy makers. When we’re discussing potential policy changes to improve outcomes for kids, we need to keep in mind how these changes will impact teachers, programs, and practices. My experience in the field as an early childhood professional helped me to think through the potential positive and negative consequences of various actions. It helped to keep us a little more real – and thoughtful about whether the policy changes are likely to do what we want them to do.”

AB: What is your vision for the future?

DK: “We would like to see state administrators throughout the country rely on the index. But I also want other researchers around the country to look at this and say – eh, you missed this. I continue to pursue opportunities to share this with other stakeholders: scholars, policy makers, and others so that we can improve it. As with any innovation, the development process takes time. While we are confident that the CCAI will be useful to informing key stakeholders, we are also confident that the way that the index is calculated will evolve as we continue to learn more about child care access and as different data become available.

Our work to this point has been focused on applying the CCAI in South Carolina, we are currently forging new partnerships with people in Florida to replicate our use of the measure and identify ways that it might need to be modified to function in a different context.

Ultimately, in the field of early childhood education, I want to move us in the direction of more data driven policy decision making. I think putting this out there in the public sphere will help drive us in that direction.”

AB: Thank you Dr. Knopf!

Story, Portrait, and Graphic Design by: Alexis Brown

Photos: CC0 Public Domain

Check Mark by Mateo Zlatar from the Noun Project